Ice, huskies and Peter & Jenny Penguin

- Nov 14, 2023

- 6 min read

The Year of the Quiet Sun: a leader’s perspective

In 1968, Adrian Hayter presented my sister Sarah and me, then four years old, with our own copies of his latest book. Recently, at the request of Antarctic magazine, I re-read The Year of the Quiet Sun and observ

ed my father’s qualities as leader of Scott Base, wintering over party 1964-5.

As a yachting journalist, I’ve written much about my father, Adrian Hayter, the first New Zealander to sail single-handed around the world. His book Sheila in the Wind about that voyage became a sailing classic. His second book, The Second Step, chronicled his military career which included his role as a British officer with a Gurkha regiment in the Second World War, being awarded the Military Cross and being made a Member of the British Empire.

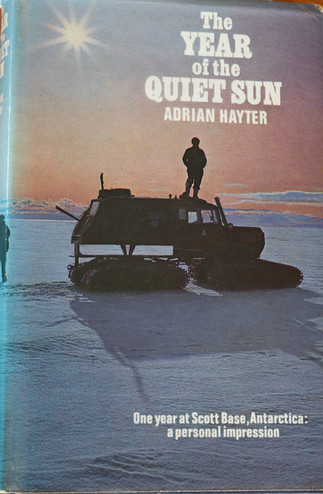

Among such exploits, his year as leader of Scott Base tends to rate just a sentence or two in his life story. His book, The Year of the Quiet Sun – one year at Scott Base, Antarctica: a personal impression, was well-received, but my sister Sarah and I much preferred his bed-time stories about Peter and Jenny Penguin. They leapt and dived between ice floes, usually with a fearsome leopard seal in pursuit.

As leader, Adrian’s primary role was to coordinate the various logistics that allowed the scientific field parties to complete their projects over summer. In 1964, it was only 15 years since he had seen active wartime service and just two years since he had completed his circumnavigation. The military had demonstrated to Adrian the far-reaching impacts of good and flawed leadership. Solo sailing had taught him to hear his inner voice and that the weather’s decision is final.

At the time, women weren’t permitted at Scott Base and, as an extreme location, it attracted a rare breed of men: staunchly independent, even eccentric. Exactly the sort of men Adrian admired. In fact, he had sought them out:

‘…during the interviewing to select candidates, I sought to choose only individualists, fully knowing the risk I took and the disintegration that could result. But Antarctica to me provided a unique opportunity to experiment in my favourite field and the need to experiment in this matter was my own deep private reason for accepting the position of Leader. I had already proven the practicality of this ideal during a lone enterprise; but now I wanted to discover whether, by applying the same principles, it could be equally practical with a group.’

The ‘lone enterprise’ referred to was his solo circumnavigation. Adrian believed the isolation of Antarctica brought the opportunity to go inward, connect with ‘self’, to trust intuition. He never undertook any endeavour without deep thought beforehand and reflection afterwards.

‘Any leader who demands loyalty from his group to satisfy his own personal motives, however these may be disguised from himself and others, will receive little real loyalty from individualists. My plan was to administer each man and task in such a way as to encourage individuality, thus placing each man in the most favourable position to discover this reward for himself, the only way it can be found. It is unique to each individual, but it is also common to all men, and being in common to all thus may become a coordinating factor as individual paths converge towards it.’

Any reader of Adrian’s books will recognise his introspective nature, but mostly The Year of the Quiet Sun is a leader’s report – the pilots’ skills in landing aircraft and taking off in marginal conditions, the field operations, his wrestling with his team’s adoration of the American way at McMurdo versus the basic facilities of Scott Base, and the agony of decision when a scientist in the field developed severe abdominal pains. I wonder now if being married to my mother, a doctor, helped Adrian to correctly suspect appendicitis and urgently request an evacuation flight from McMurdo.[1]

So his conclusion to The Year of the Quiet Sun is the place for Adrian Hayter philosophy:

Only on the completion of an experience, and perhaps with removal from it to another environment, are we able to observe it and draw sensible conclusions. My own deepest impression of Antarctica now is the fact that the values we lived there often contrasted so sharply with conventional values practised elsewhere.

One of his favourite sayings was: ‘Inflexible in principle, flexible in application.’ It makes a brief appearance in The Year of the Quiet Sun, albeit thinly disguised. Another was the belief that for harmony to exist, the giving and receiving must equate. That shaped his objections when members of his team casually borrowed items from McMurdo.

Which leads to another aspect of Antarctica that resonated with Adrian: it’s never seen war and is the only continent on Earth unowned by any country.

‘Heaven knows we had our disagreements at Scott Base, often due to my own faulty leadership, when the drop in the team’s morale made it obvious that I was on the wrong track. But somehow we stuck together, the men themselves carrying me through my periods of failure, and I came away with the belief that if those principles are practical when applied to a small isolated group, then those same principles would be equally successful if reapplied to a nation. This of course is democracy, which today is claimed by many but in truth is practised by none.

I believe that in that strange awareness which may be found in Antarctica rests that other sacred half necessary to complement our materialism and technology, to bring more sense to our world as a whole. And to fill this need is why some men go South, if only because the continual invasion of our privacy makes it almost impossible to find at home. I also believe that this secret key, if understood, is the most valuable discovery ever likely to come out of Antarctica.

I don't believe Adrian is saying that everyone needs to go to Antarctic to achieve a greater understanding, but that we do need to go to a place of isolation. And, to come back.

My earliest memory is of being on my mother’s hip and my father smiling as he walked towards us across tar seal. Maybe it’s the creation of a child’s whimsy, but in my mind, he had just returned from Antarctica.

Three years later, the Newmans bus dropped off a cardboard box outside our house at Upper Takaka. Adrian placed it on the dining table and cut the string with a pocket knife. I still sense his quiet thrill of anticipation as he held the first copies of The Year of the Quiet Sun. In my copy he wrote: For Beckie, for when she grows up.

For all the articles I have written about my father, this is the first time I’ve written specifically about his time at Scott Base, so, as a grown-up, I re-read The Year of the Quiet Sun.

Many of us in our careers accommodate the skills and flaws of our leaders. Many leaders/managers are happy just to hit the performance targets and stay on the right side of the HR department. But Adrian was a conscious leader. He had a requirement at Scott Base that if anyone came to him with a problem, that they also brought at least one possible solution – a tactic that often meant the man resolved the problem himself. Adrian constantly monitored his own performance against team morale, individual motivation, and was aware of each man’s dilemmas in regards to his family in New Zealand versus his responsibilities at Scott Base.

Adrian must have felt that dilemma keenly when he received a message from my mother, via the Antarctic Division, to say that I’d drunk kerosene from a soft drink bottle I’d found in a friend’s garage. In one version of the story, the message got garbled and reported that I’d died. The all-clear came through a day or two later. Adrian doesn’t mention it in The Year of the Quiet Sun, and probably didn’t mention it to anyone at the base.

So, how did Adrian’s peers evaluate him as leader of Scott Base? For his 50th birthday, one of the field parties, officially the New Zealand Geological Survey Antarctic Expedition 1964-5, arranged to gazette the 2,690m (8,830ft) Mount Hayter. To be fair, they were naming several features for their friends at the time.

In Adrian’s papers, I found an undated telegram from Jehu Blades, officer-in-charge at McMurdo:

1. Upon completion of the wintering period at this station I want to express my profound appreciation for the outstanding cooperation of the men of Scott Base under the exceptionally capable leadership of Major Adrian Hayter.

2. Under the trying conditions of isolation and a hostile environment when close cooperation is essential and yet not always easy to achieve, mutual problems were invariably resolved effectively and amicably thanks to the wide experience and skill of Major Hayter.

3. The many services, such as the voluntary training of our search and rescue group by Scott Base experts, which have been rendered to us have done much to further the accomplishment of the mission of this station.

In 1970, Adrian was awarded the Polar Medal for services to Antarctica.

But the real score sheet came from the men of Scott Base, many of whom remained close friends with Adrian until his death in 1990. At Adrian’s request, his deputy leader, Mike Prebble, was one of his pall bearers.

As for me, I’ve never been to Antarctica, but I know that among the creak of crevasses is a sparkling ice shelf, the magical home, the secret wisdom of Peter and Jenny Penguin.

© Rebecca Hayter

Reprinted courtesy of Antarctic magazine, www.antarcticsociety.org.nz

Comments